teams

The Subculture of Innovation

Subcultures are often thought of in a corporate environment as evidence of fragmentation of the organization or a failing of management to impart a compelling collective vision. Some have argued that strong organizational cultures, where members agree and care about an organizations values, almost preclude the formation of subcultures[1]. There is significant evidence however, that even within the most successful organizational cultures there can exist, and sometimes must exist, strong subcultures in order to provide the mechanism for adaptation and change. In the same way that the innovative company creates change in the world, the innovative sub-culture creates change within a company.

Subcultures are often thought of in a corporate environment as evidence of fragmentation of the organization or a failing of management to impart a compelling collective vision. Some have argued that strong organizational cultures, where members agree and care about an organizations values, almost preclude the formation of subcultures[1]. There is significant evidence however, that even within the most successful organizational cultures there can exist, and sometimes must exist, strong subcultures in order to provide the mechanism for adaptation and change. In the same way that the innovative company creates change in the world, the innovative sub-culture creates change within a company.

The evidence for subcultures within your organization will be all around you. A few years ago I had an opportunity to meet with a large advertising agency and spent a few hours observing the differences between the very diverse people that can populate that industry. What struck me most were the well defined dress styles that each group adhered to in order to define themselves as being part of their own subculture. The creative tribe had their style (well pierced street fashion) and the business development tribe had their style (no tattoos, no jewellery, nice suits)and it was immediately obvious who was who. Returning to my office later in the day I could see the same tribal dress (with much reduced flamboyance) in the staff I spent most of my time with.

In some instances companies rationalize subcultures as the price of doing business, “you can’t expect artists to wear suits” or “you have to supply programmers with mini refrigerators” are themes that we might be familiar with but which infer that subcultures are necessary but not ideal. Looking at some of the more diverse organizations however we often see examples of subcultures being nurtured, not just reluctantly accepted, maybe the most successful example would be Lockheed’s Skunk Works group. Can other large corporations learn from this?

In some instances companies rationalize subcultures as the price of doing business, “you can’t expect artists to wear suits” or “you have to supply programmers with mini refrigerators” are themes that we might be familiar with but which infer that subcultures are necessary but not ideal. Looking at some of the more diverse organizations however we often see examples of subcultures being nurtured, not just reluctantly accepted, maybe the most successful example would be Lockheed’s Skunk Works group. Can other large corporations learn from this?

Subcultures and Corporate Innovation

In most corporate environments innovation is not a priority for all employees. No matter how sensationally the “We are Innovative” PR machine spins, when pressed we all have to admit that an extremely large proportion of our collective time is spent maintaining the status quo. We all work in extremely competitive environments and to ignore the effort that is required just to avoid going backwards is an injustice on those who have this as their primary responsibility.

One concept we love at Osmotic Innovation is that corporate innovation is best done by those who choose it, rather than those conscripted. How this concept can manifest within the organization is the formation of ad-hoc innovation teams, matrix managed programs, skunkworks (in the adopted sense) and the many people from operations outside of formal innovation roles collectively bringing their ideas to life.

How then can the Osmotic Innovator use subcultures to support and nurture innovation within an organization? Rather than taking the direct (and somewhat ambitious) approach of trying to generate sub cultures themselves perhaps it is simply a matter of loosening up. Subcultures will form where a group of people have a shared opinion that differs from the collective paradigm. Where they flourish is in environments where they are allowed to express their differences, that is, where an organization lets them and encourages them to be different. Innovation as we mentioned earlier is by and large a fringe activity within most large organizations and so is an ideal activity to be the rallying point for sub culture formation. By loosening up some of the organizational cultural norms the Osmotic Innovator empowers the subculture to define itself and thus achieve in the light of day rather than in secret. Your innovators will identify themselves if you allow them to; just give them their own space, their own time or simply the freedom to dress themselves in the morning.

[1] Alicia Boisnier, Jennifer A. Chatman The Role of Subcultures in Agile Organizations. Accessed Sep 2012. http://www.hbs.edu/research/facpubs/workingpapers/papers2/0102/02-091.pdf

Project Management and the Art of Storytelling

Innovation projects within corporations can take a long time, a really long time. These projects often involve lots of people and even numerous ownership changes along the way as different specialist groups contribute their skills. Managers are very much aware of this however and have any number of great modern inventions to manage the risks associated with long project leads, knowledge transfer and project ownership. Just think of the highly detailed Gantt charts, the agile management tools, the strategy meeting minutes and risk analysis reports that reside on your corporate servers, all testament to the pinnacle of project management that we have reached in the early 21st century. Because of all these modern tools it is now impossible for a project to deviate off course, to lose its way and end up in a place that was not intended. Modern project management techniques ensure that we always deliver what we started out to deliver and the economy and the world is a better place for this. Wait…what?

Innovation projects within corporations can take a long time, a really long time. These projects often involve lots of people and even numerous ownership changes along the way as different specialist groups contribute their skills. Managers are very much aware of this however and have any number of great modern inventions to manage the risks associated with long project leads, knowledge transfer and project ownership. Just think of the highly detailed Gantt charts, the agile management tools, the strategy meeting minutes and risk analysis reports that reside on your corporate servers, all testament to the pinnacle of project management that we have reached in the early 21st century. Because of all these modern tools it is now impossible for a project to deviate off course, to lose its way and end up in a place that was not intended. Modern project management techniques ensure that we always deliver what we started out to deliver and the economy and the world is a better place for this. Wait…what?

So, I expect that you agreed with most of the above paragraph until maybe the last few sentences. Most of us have experienced a project deviating from its goal, maybe through a slow erosion of the understanding of the original intention, claim creep over time or a simple loss of way due to personnel change at a key juncture. In our arsenal of modern project management tools is there something missing that might help us eliminate this issue? If not, should we be developing something? I suggest that there is a tool that can be used to help corporations but that it won’t be found in Silicon Valley. The tool is as old as humanity and within us all to develop. It is the art of storytelling.

Throughout history humans have managed projects. Our earliest projects may have been something like relocation of tribal groups or the exploitation of newly found food sources. During this time the project management tool most often used was storytelling (Note: This is an assumption the author has made based on the lack of Neolithic cave paintings depicting Gantt charts). Storytelling allowed complex themes with numerous important yet discrete facets to be remembered because it provided context and a relationship between the discrete elements of the theme. If Timmy isn’t stuck down the well, Lassie is just a dog running around barking and doesn’t make sense.

Throughout history humans have managed projects. Our earliest projects may have been something like relocation of tribal groups or the exploitation of newly found food sources. During this time the project management tool most often used was storytelling (Note: This is an assumption the author has made based on the lack of Neolithic cave paintings depicting Gantt charts). Storytelling allowed complex themes with numerous important yet discrete facets to be remembered because it provided context and a relationship between the discrete elements of the theme. If Timmy isn’t stuck down the well, Lassie is just a dog running around barking and doesn’t make sense.

So how can we incorporate storytelling into our project management programs? The solution is to first think about what modern storytelling looks like. In the context of a consumer product, the story might take the form of an advertisement, maybe in video or billboard form. It could take the form of a written consumer concept or a cartoon describing the experience of the consumer. A service story might be told through the written diary of a satisfied client or mock interview. In many cases our companies are quite adept at making these stories; we just tend to make them once a project is nearing completion which renders the use of the story as project management tool redundant. The key thing that any storytelling tool should do is allow for a simple, understandable way to communicate project goals and underpinnings to new team members or management reviewers. It should enthrall and energize the project and ensure that throughout the various personnel transitions each new member champions and rallies around the common and original goal. Next time you kick off a big project consider developing some story media early on in the process, you will be surprised at the effect it can have.

Playing the Fool for Innovation

When most companies build their staff they focus on identifying the best talent in their industry, proudly trumpeting this as both a reason to join their company and for stockholders to take heart in their capacity to stay ahead of the competition. As discussed previously in this blog this can lead to a very narrow focus within a team, limiting diversity of thought. Can an organization work around this by finding someone that can force teams to stretch outside their comfort zones while still being a productive and regular member of the team?

When most companies build their staff they focus on identifying the best talent in their industry, proudly trumpeting this as both a reason to join their company and for stockholders to take heart in their capacity to stay ahead of the competition. As discussed previously in this blog this can lead to a very narrow focus within a team, limiting diversity of thought. Can an organization work around this by finding someone that can force teams to stretch outside their comfort zones while still being a productive and regular member of the team?

In fact, the skills required for this role have been recognized for millennia. In mythology, stories are full of trickster gods that challenged the status quo, whose role seemed on the surface to be spreading discord. Take Loki from Norse mythology. In the stories, he appears to fill many roles and is even able to take many forms as a shape shifter. His role is not to govern but rather to disrupt and to agitate. Alternately the other gods love and hate him. The role of Loki is as an antagonist – his appearance in a story drives it forward and forces the other gods to take action. Even today scholars debate his intent in the stories – his presence still causing discord, discussion, and ultimately ideation. The trickster figure is complicated in myth – they are often seen as rule breakers, sometimes malicious and sometimes not, but often to positive effect. They are problem solvers and deliver solutions – often times being the source of the innovation of fire.

Even the stolid courts of the medieval period recognized this skill: the “fool” was expected to not only be funny, but to also deliver insightful and truthful commentary that would allow the leaders to more thoroughly see the world. This was the living embodiment of the trickster, an antagonist that creates change through disruption.

But what type of person can serve as the trickster or fool on your team? How can a person like this fit without being a disruption to the team and group dynamic. I would propose that this role can be filled by what we’d know as a generalist. The generalist is an individual with broad knowledge. Much like Thomas Jefferson or Benjamin Franklin they can fill multiple roles and careers in their life, having interests as broad as writing a new bible, creating a university, and governing the nation in the former case and writing and publishing (including the everything-you-ever-needed-to-know Poor Richard’s Almanack), amateur science, and diplomacy in the later case. The generalist has knowledge on a variety of topics, being conversant in them while having the ability to learn and acquire subject matter expertise quickly in order to leverage their broad base of knowledge.

The generalist must also have the confidence to speak up. This is because the generalist also benefits through naivety – unencumbered by the certain knowledge of the status quo they are able to call it as they see it. When an idea has no clothes, but those close to the industry or technology are unable to recognize it, the generalist can demonstrate true sight, asking questions and revealing truth that will allow others to recognize something that can (with hindsight) seem rather obvious.

Retaining this skill is difficult though. The generalist is at a disadvantage to peers with expertise and experience in a field and needs to have the confidence and personality to speak their mind in the face of a well-organized and entrenched opposition. Further, the complex nature of the Fools role requires them to be a very special individual, curious enough to question every detail, competent enough to understand a vast array of topics, skilled in communication to deliver their true message, and social enough to be welcomed into a team without being a threat. Ignoring this critical role can ensure that your team smoothly rockets toward mediocre innovation. Having a powerful voice in this role can boost the productivity and quality of output exponentially. The successful Osmotic Innovator knows how much resource a fool can save through practical knowledge, common sense, and deep insight. The question isn’t how to get rid of the fool on their team, but how to get more of them.

Retaining this skill is difficult though. The generalist is at a disadvantage to peers with expertise and experience in a field and needs to have the confidence and personality to speak their mind in the face of a well-organized and entrenched opposition. Further, the complex nature of the Fools role requires them to be a very special individual, curious enough to question every detail, competent enough to understand a vast array of topics, skilled in communication to deliver their true message, and social enough to be welcomed into a team without being a threat. Ignoring this critical role can ensure that your team smoothly rockets toward mediocre innovation. Having a powerful voice in this role can boost the productivity and quality of output exponentially. The successful Osmotic Innovator knows how much resource a fool can save through practical knowledge, common sense, and deep insight. The question isn’t how to get rid of the fool on their team, but how to get more of them.

Implementing Culture Change to Drive Innovation

As discussed in a post last week, innovation is in part a cultural phenomenon – something that is in a lot of ways the antithesis of the culture that naturally appears in a successful firm over time. But its easy to change the culture to harness innovation, right?

As discussed in a post last week, innovation is in part a cultural phenomenon – something that is in a lot of ways the antithesis of the culture that naturally appears in a successful firm over time. But its easy to change the culture to harness innovation, right?

You can’t be blamed for believing this, with the plethora of books and management consultants touting numerous ‘can’t fail’ ways to change the company culture from the CEO down as a way to boost innovation and create a renewed energy. Unfortunately, this is a lot easier said or written about than done. And what about those of us that work in a company that either thinks it is already innovative enough or has no interest in changing what works now for the larger corporation? How can an individual create real organizational change to increase and drive innovation without the power of the CEO to direct internal marketing campaigns and HR efforts?

As companies grow they require increased systems, processes, and hierarchy in order to manage the growth and control profitability. Eventually, this driving force becomes self-sustaining – with success comes bureaucracy (perhaps necessarily) and people that function well within a structured and organized environment. Eventually those innovative and driving employees that were the root of the success of the company either change to fit into the new dominant culture or are forced out. We justify this by saying that they aren’t a cultural fit anymore. At some point though in the progression of most firms it will become necessary to shift the culture to recapture that innovative spirit, at the very least within individual business units or groups that are looking for growth and new opportunities.

To understand how to impact the culture to improve innovation we must first understand two aspects of culture that can limit innovation:

Shared Beliefs: In most organizations, as a result of the filtering process that occurs during hiring and induction and that continues through teams shared experiences a strong set of shared beliefs will appear. These can be a strong tool to strengthen a corporation, leading to more delegation, decreased monitoring, higher satisfaction, higher motivation, faster coordination, and more communication, but importantly, also to less experimentation and less information collection.[1] Experimentation and information gathering are at the core of innovation, so while shared beliefs can be great for the corporation they can also severely limit innovation for a team.

Focus on Process Excellence and Cost Cutting: As stated above, a successful firm will have developed a strong bureaucracy by the time change for innovations sake is necessary. A focus on strong process excellence and cost cutting (along with out-sourcing and quality) are essential to deliver consistent returns to Wall Street. However, they are also an enemy of innovation as they look to eliminate complex projects that don’t fit the model and discourage high risk activities that require investments of time and money.

Focus on Process Excellence and Cost Cutting: As stated above, a successful firm will have developed a strong bureaucracy by the time change for innovations sake is necessary. A focus on strong process excellence and cost cutting (along with out-sourcing and quality) are essential to deliver consistent returns to Wall Street. However, they are also an enemy of innovation as they look to eliminate complex projects that don’t fit the model and discourage high risk activities that require investments of time and money.

Knowing that these two things; Shared Beliefs and Focus on Process Excellence and Cost Cutting are major parts of the problem is only the start. How might the Osmotic Innovation change their team using this knowledge?

Disrupting Shared Beliefs: One cannot eliminate all sources of shared beliefs – so long as employees work together they will gradually build this characteristic. However, manager selection of employees plays a very strong role in sustaining shared beliefs. By selecting employees that are ‘culture fits’ or that think like the manager they sustain and strengthen this culture. Hiring people that are viewed as cultural risks while having the right skill set is one possible way to shift shared beliefs to encourage more experimentation and information gathering. Note that these should be people in important positions – having a few crazy technicians won’t disrupt the way that a group of managers or senior scientists think. It has been shown that culture and shared beliefs tend to flow from the important people within an organization so an even easier mechanism might be to put those who are willing to buck the status quo in your current organization into positions of responsibility and power or appoint them to take a lead on innovation initiatives.

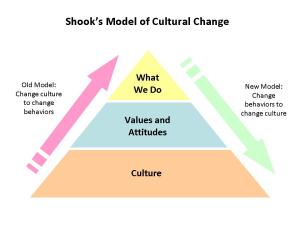

Really Focus on Innovation: Because most employees see their compensation and reward systems being tied to the values of process excellence, cost cutting, and quality finding time or initiative to work on innovation or the willingness to support high programs is unlikely. Instead innovation needs to become part of everyone’s day-job, and should be tied to their annual performance / compensation reviews. This shows the commitment to innovation that can encourage creative employees to begin committing to new ideas and innovation. As was learned in the 1980’s at the joint Toyota-GM NUMMI venture, changing culture starts with changing what people do – the new way of thinking will come.[2] John Shook has described this in a model based on Edgar Schein’s original model of corporate culture; shown to the right.  Apply this lesson by making employees responsible to deliver innovation as part of their job function. The new way of thinking (and culture) will follow. Merely advertising a new motto or idea to change peoples thinking isn’t enough to change values and attitudes and what people really do.

Apply this lesson by making employees responsible to deliver innovation as part of their job function. The new way of thinking (and culture) will follow. Merely advertising a new motto or idea to change peoples thinking isn’t enough to change values and attitudes and what people really do.

Short of wholesale changes driven by the CEO and Board, culture change to increase innovation can be managed and implemented within smaller parts of the organization by recognizing the key factors that drive and develop culture. Disrupting the entrenched belief systems to encourage experimentation and new knowledge gathering along with making innovation a measured part of a teams job function can be the levers used by the Osmotic Innovator to change a team or organizations culture from the ground up.

Embracing your Trapeze Artist

Diversity of thought within corporations is a key driver of innovation. This statement is rarely challenged by those charged with building the innovation programs of companies but how often does this need for diversity actually impact the way companies hire and retain their staff base? Often the culture of a corporation is thought of as a sort of open window, allowing many diverse individuals through and only imparting influence on their behaviors and attitudes once the individual is employed.

While this argument may be reasonable for some functions where skills are readily transferable across many different types of businesses, the key participants in your corporation’s innovation program are far more likely to rely on a very similar combination of education and experience to perform highly. This in turn means that the effect of culture of a corporation is more like a filter than a window.

If thought diversity is a driver of successful innovation we must then recognize that the culture inherent to our innovation programs constrains the diversity available for these programs. Common phrases such as “culture fit is the most important factor for career success around here” or “hiring a (non core specialist) is an indulgence we haven’t the resource for” are the verbalization’s of this in action.

What happens then is that you have a program full of common professionals, maybe scientists, engineers and marketers and, while there may be some variety of thought within this narrow segment, more often than not this will pale in relation to the diversity of thought in the larger world. Think of the circus – a bunch of highly creative artists who probably see the lion tamer as the dour authoritarian compared to a pharmaceutical company where the chemist who rides a motorcycle is seen as the risk-taker by the others. The culture in these places necessarily filters the employees and creates a narrow band of thought. However big that band appears from inside it is still a narrow band.

What does this mean for your innovation program? Should you immediately go out and recruit a trapeze artist to broaden your culture? The reality is actually far simpler; your company culture acts in both directions, the trapeze artist is no more likely to apply for your vacancy as you are to join the circus. Where an awareness of diversity constraint can help your program is on the odd occasion where a genuinely divergent thinker has made their way through your company’s filter. This can occur through the recruitment of a massively talented individual whose divergence is tolerated for their skill set but more often it is the result of the normal changes in attitude and motivation that engaged employees experience over time. Unfortunately in many corporations the career path of the divergent thinker is often less than stellar and rather than encouraging this diversity the individual ends up facing a “conform or leave” decision. Within your innovation program however these people are like gold. To bring a different “thought world” to your program while still feeling they have a place within your company is a rare set of circumstances and should be recognized as such. The challenge for the innovation program manager is not in helping them conform but in maintaining their non-conformity. To get the most out of their novel perspective they should also be put in high contact roles with other groups, something that can sometimes feel counter intuitive to a manager. Managing thought diversity to improve innovation is an opportunity that only larger corporations, with significant division of labor can hope to achieve. Unfortunately it is also one opportunity that is most easy to ignore.

Osmotic Innovation is Linking You Up

The Five Personalities of Innovators

According to this article by Brenna Sniderman published on Forbes.com the most successful teams include all five personality types. Click through to read about Movers and Shakers, Hangers-on, Experimenters, Star Pupils, and Controllers. Which are you and which are missing from your team?

Is Working for a Corporation Better?

The team at Fast Company gives 9 reasons you should work at a corporate job rather than a start-up. We’ll let the author, Jeetu Patel, sum it up; “Startups can be amazing places to work, and the euphoria surrounding them has a high degree of contagion. But future leaders have unique lessons to learn by working for larger, more established companies as well.”

In previous blogs, we have explored the topic of groups and interactions among people and have described the drawbacks as well as importance of including people from outside a specific type of organization. In this article, Jose Baldaia provides an argument on the importance of a team and the power of the contributions it can provide to a company.

The Role of Psychological Priming in Innovation

I have a rather unique ability. I have the power to potentially alter your behaviour and perception of others by simply showing you a list of words. Impressed? Don’t be. In actuality I am simply applying a psychological technique called priming. Academically, priming is defined as “the process by which recent experiences increase the accessibility of a schema, trait, or concept.” Sounds confusing, but in reality it is very simple to understand. Imagine if I were to provide you with words like rude, intrude, and disturb to unscramble and then ask you to come get me when you were done. Upon completion of the task, you find me but notice I am having a conversation with a colleague. Would you immediately interrupt me or wait a few seconds? What if the words were patiently, appreciate, and polite? Would that alter your behaviour? Surprisingly, in a study performed by John Bargh and his associates, participants primed with aggressive and rude words overwhelmingly interrupted the conversation faster than people primed with either neutral or calmer words[1]. This is just one example from Social Psychology that demonstrates how our actions and thinking can be skewed based on how we are primed prior to encountering an event.

If we now think about the potential application to innovation, there is something rather interesting that comes to light. In any innovation session there exists a potential struggle between Management and the Employees. Management oversees the resources needed (e.g.: funding, personnel, allotment of time) while the Employees are the ones who will do the innovating. Should we consider a negative primer to something like the phrase “This is a very difficult innovative challenge and we may not get a lot of ideas”, a positive primer would then be along the lines of “This will be a rather easy innovation challenge and we should be able to get lots of ideas”. What if we were to use the negative primer for Management and the positive one for the employees? Would that provide a better innovative atmosphere? How about changing the combination and providing management with the positive primer and employees with the negative one? If we were to map out all the possible combinations, we obtain the following diagram:

There are several situations that can result from different combinations of positive or negative priming.

There are several situations that can result from different combinations of positive or negative priming.

Management Positive Primed: Trying to impress Management by informing them the innovative challenge will be easy counter intuitively produces a negative outcome as there will be limited funding and personnel.

Management Negatively Primed: This produces a positive result, as Management will now think the task is rather challenging and in order to successfully complete it, will provide extra funding and personnel.

Employees Positively Primed or Negative primed produces the results we would expect. Telling Employees they have been selectively chosen for the challenge due to their skill level and creativity will obviously produce a group that is very motivated and enthusiastic to take on the challenge. As one can easily guess, the opposite will occur if Employees are told the challenge will be rather difficult, many problems will be encountered along the way, and they were randomly selected.

Clearly there appears to be a combination that is optimal for an innovative environment: more resources are provided and the employees are very enthusiastic. This lies in priming management in a negative way and priming Employees in a positive way. As mentioned, this paradoxically should result in a situation where funding and/or additional resources are provided to an eager bunch of innovative employees waiting to take on the challenge. Imagine if all your problems were approached in this way!

There is also a situation that should be avoided. If management is positively primed, and Employees are negatively primed, low levels of resource and funding will be provided and you will end up with a bunch of Employees who do not want to take on the innovative challenge.

It can be agreed upon how either of the remaining two combinations (e.g. positive primer to both Management and Employees/negative primer to both Management and Employees) is what a typical company usually faces when an innovation challenge is encountered. Either there will be excited management ready to give money, time, etc to unmotivated and overworked employees, or very excited employees who want to work on a particular challenge will be told they have very strict limitations. However, as demonstrated above, perhaps utilizing psychological priming may decrease this tendency and help to promote a more positive innovative culture.

[1] Bargh, J., Chen, M., & Burrows, L. (1996). Automaticity of social behavior: Direct effects of trait construct and stereotype priming on action. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 71, 230-244.

Creating an Effective Innovation Group

In the growing competitive corporate environment, the demand for new innovative products that help drive growth becomes of vital importance. In Businessweek magazine[1]IBM CEO Samuel J. Palmisano was quoted as saying “The way you will thrive in this environment is by innovating – innovating in technologies, innovating in strategies, innovating in business models”. This sentiment is echoed in companies like Google, Nissan, and Apple to name a few. Therefore, to meet this demand it is rather common for most companies to conduct group innovation sessions. Considering this, the question then is how we can create an effective innovative group?

In the growing competitive corporate environment, the demand for new innovative products that help drive growth becomes of vital importance. In Businessweek magazine[1]IBM CEO Samuel J. Palmisano was quoted as saying “The way you will thrive in this environment is by innovating – innovating in technologies, innovating in strategies, innovating in business models”. This sentiment is echoed in companies like Google, Nissan, and Apple to name a few. Therefore, to meet this demand it is rather common for most companies to conduct group innovation sessions. Considering this, the question then is how we can create an effective innovative group?

In creating this, one of the most important steps is in choosing the participants. But what kind of person are we exactly looking for? There are numerous personality type tests one can use to either screen job applicants, or better understand the people within an organization. With the demand placed on innovation it is no surprise that 80 percent of fortune 500 companies use some kind of personality test, with Myers-Briggs Type Indicator being most favoured, according to an article in Psychology Today[2]. These tests not only have their pros and cons in the Psychology community, but they can also be expensive and most likely need a professional to administer. Therefore, I propose a more simplistic approach in modelling a group and deciding participants.

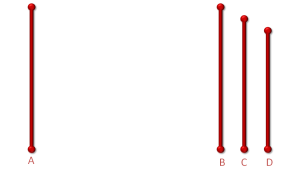

For the sake of simplicity, lets draw a line representing personality types and on the left side label it “Very Artistic” while on the right side we place the label “Very Structured”. Who might we place on the left side of our graph? Most likely “Very Artistic” conjures to mind those who are artists, dancers, improve actors, and anyone else with a talent or career that is solely dependent upon bringing to life limitless imagination. Therefore, on the opposite end of the spectrum, defining “Very Structured” becomes rather easy: Accountants, Engineers, Mathematicians, or any type of person who is either drawn to a very structured environment or has a very structured career. We can then consider the span between these two extremes as the degree to which someone is near either one – taking into consideration possible outside talents, interests, level of education, etc. In thinking of a group structure, there will be varying levels of intensity toward either end, so the use of a box will perhaps best capture this. For example, consider a company that is primarily focused on manufacturing and selling chemicals. I’m sure we can all agree that such a company would likely have a research and development group containing a large percentage of people with some kind of focused technical background. We can then pictorially represent this by placing a box near the “Very Structured” side (Figure 1)

On the other hand, consider a Theatre company employing a group of interpretive dancers. In this case, one would expect most of them to be somewhere near the “Very Artistic” side and so with a box placed there, our graph would then look a bit like Figure 2.

On the other hand, consider a Theatre company employing a group of interpretive dancers. In this case, one would expect most of them to be somewhere near the “Very Artistic” side and so with a box placed there, our graph would then look a bit like Figure 2.

In looking at the differences between the two examples, it can be hypothesized that the nature of a corporation essentially preselects the members of that group and therefore makes obtaining people from different end of the spectrum rather impossible.

Therefore, with use of such a model to describe the dominant nature of a group, one can then ask: is it advantageous to select people strictly from within the group, or would it be more valuable for the company to have a sampling from different locations on the graph?

Should we primarily select within a particular segment of the spectrum, we know we would get people who share a similar educational background and interest in the field they have a career in. However, although a broad commonality is shared, each one of us is unique and brings to the table a spectrum of emotional and intellectual diversity that in of itself may be sufficient enough to tackle the challenge at hand. Ask the participants about their hobbies outside of work and somehow incorporate that into the session. Discover more about the people in the session and tap into their previous experiences and talents. Using such methods will certainly bring something different to the innovation session, but the facilitator must still be wary of how immersed they are in the challenge. Often times, even with these techniques, it is a bit difficult to get people thinking outside of what they are familiar with. This brings me to the next (and personally preferred) method: inviting people outside the group.

In contrast to selecting within the group, we can consider the option to select people from different locations along the plot that exist outside the group. In doing this, a wider array of creativity and alternate viewpoints can be introduced. Think of what would happen if someone like a magician were to attend an innovation session being conducted by an engineering firm. Would doing this successfully contribute anything? If we consider the art of Magic, there is clearly lots of innovation and creativity that goes into any small to large illusion. Therefore, one way to utilize someone like this would be to have them perform a few small tricks. After each one, the engineers would be challenged to try and think of different ways it could have been accomplished. In doing this, the engineers will essentially be solving a rather unique puzzle while getting their minds primed to think in a different way. Have the magician then reveal the trick and allow the group to discuss the different ways they approached an explanation to what they just saw. This is just one example of taking someone near what we termed “Very Artistic” and placing them into the group that may be more near the “Very Structured”. I am sure with a bit of your own creativity you can come up with other examples.

With both options discussed, is one technique better than the other? I challenge you to come to your own conclusion, but to those who think something very specific and technical is best solved by a room of PhD’s using complex equations – remember one important thing: Kekule daydreaming about a snake biting its own tail provided the structure for Benzene, which at the time revolutionized the field of Organic Chemistry.

Decreasing Conformity in an Innovation Session

If I were to ask you to quickly recall the last session you went to, most likely the first thing you will say is “Well, a group of us got together and…” You will probably then continue to focus on what activities were done, where you went, and the results that were obtained. However, a critically important component is often overlooked – the effect of the group on an individual. Are individuals in a group setting really contributing to the best of their abilities? Yes, we all know there are the introverts and the extroverts, but despite that we still get the best from each person, right? Don’t be so sure.

Consider the Solomon Asch conformity experiment: A straight line was shown to a group of college students who were all in on the experiment except for a single test subject. In the test, a card with a straight line (line A) was shown, followed by a card with another set of lines (lines B,C,D). When asked which line is closest to A, all the students who were part of the experiment were instructed to purposefully give the wrong answer (line C). Because the experiment was preceded by several sets of cards where correct answers were given by the group, and trust established, the test subject was in a position of distress: follow the group or give the correct answer? Over-all, the test subject gave the wrong answer (line C) 32% of the time. During the course of repeating the experiment, about 75% of the time the subject conformed at least once. Only rarely was an individual observed who gave the right answer (line B) each time, while there was a minority (5%) that conformed to the group every time.

Experiments like this one and others that have been conducted in the field of Social Psychology demonstrate “Conformity”. According to Elliot Aronson, author of The Social Animal, conformity is defined as “a change in a persons behaviour or opinions as a result of real or imagined pressure from a person or group of people.” There are several factors that contribute toward conformity, but for simplicity, the main factor to consider is the desire for one to be accepted by his/her group of peers. Considering this, the question for the innovator becomes one of how can we lessen this tendency and encourage more individuality when placed in a group setting?

The answer depends to a large extent on how the innovation session is conducted. There are numerous techniques to engage people and bring out their creativity that are readily found in books, online, and even from professional facilitators. Everything from the colour of the room to specific physical activities has been reviewed at one time. However, one thing not often addressed is how to decrease conformity in a group and nurture an environment where individuals can contribute more to the innovation session.

Ok, so now what? How do we do this you ask? As one may expect, the size of the group has an effect on whether or not someone conforms to the group they are in. As Rod Bond from the University of Sussex[1] describes, a maximum of 3 to 5 people induce this behaviour (with 5 people being where it levels out), while groups of two drastically reduce the effect. This also ties into the next point: having an ally. In a variation of the experiment conducted by Asch as previously described, one of the students acted as an ally to the test subject. Just as before, all the students gave the wrong answer except for one student who was instructed to give the correct answer. In this situation, when the time came for the test subject to provide an answer, the correct one was given. What happened? The pressure to conform was drastically reduced. What does this tell us? Try breaking your large group into smaller groups of two to accomplish a task. Encourage those paired up together to share something funny about themselves. In doing so, you will not only help people create an “ally”, but conformity will have been reduced because you have broken down the larger group.

Some other things you may want to try:

- Break a complex problem down into smaller, more manageable parts. Typically when members of a group are uncertain about a problem, they begin to look to others for confirmation.

- Conduct innovation sessions without the presence of either someone of authority (e.g. Managers or Directors) or an expert in the field that is the focus of the innovation session. This will reduce the tendency of others in the group to look to such figures of authority for approval by agreeing with them.

- Create an activity where members need to make a commitment to their initial judgment, idea, or response. In doing so, their probability to change their mind or conform to the group will greatly decrease.

Why is this important for innovation sessions? Think about it: the Asch experiment drives home that in a typical session, there is a high probability that people will not be giving their own true answer or contribution. By using these techniques, the innovation session facilitator can likely maximize the contribution from each person and hopefully obtain even more ideas and increased levels of creativity.

Resources

Aronson, Elliot. The Social Animal. 10th ed.New York: Worth Publishers, 2008.

Gleitman, Henry, Alan J. Fridlund, and Daniel Reisberg. Psychology. 6th ed.New York: Norton, 2004.

[1] Bond, Rod; Group Process & Intergroup Relations, 2005 Vol 8(4) 331-354

Are Start-Ups More Innovative Than Large Established Firms?

Start-ups are typically considered to be free-thinking, risk-taking, and open-minded – characteristics that are universally agreed as necessary for incubation of radical or disruptive innovation. Meanwhile large companies are viewed as too results-focused and risk-averse to create anything besides slow incremental innovations. Is this commonly-held assumption truth or fiction or something in-between and are start-ups or large firms better positioned to successfully commercialize innovation?

Who or where you ask these questions will generally inform the final answer. At most big corporations they focus on the extremely high failure rate for start-ups (even the ones that obtain VC funding) while in the converse situation they’ll point to the radical or disruptive work done by Twitter and Facebook and compare it to the relatively incremental product improvements being churned out by their larger counterparts.

In “Why Small Companies Have the Innovation Advantage”[i] Sam Hogg argues that small companies are more innovative because, besides differences in culture (valuing entrepreneurship more highly) and organizational structure (making faster decisions), they are built to take risks that a larger company cannot justify. However, justifying innovativeness based on risk tolerance alone just doesn’t make sense. The counter-argument could be made that big companies have a better process to balance risk – by ensuring that innovative projects with the highest potential for success are funded while those that do not meet internal standards are killed or allowed to leave for external development (where failure cannot hurt the bottom line) or that bigger companies are better positioned to understand their markets.

This counterargument leads to a point made regarding 3M in a past Schumpeter column in The Economist[ii] – that large companies “can combine the virtues of creativity and scale. 3M likes to conduct lots of small experiments, just like a start-up. But it can also mix technologies from a wide range of areas and, if an idea catches fire, summon up vast resources to feed the flames.” If one is to take this side of the discussion fully, one then assumes that large companies have the knowledge and resources to determine what areas to work in and which ideas to fund toward development and thus have the advantage in innovation.

That entrepreneurial people can have a bigger impact by leveraging the resources of a larger company to drive innovation is a sentiment shared by no-less than Sean Parker[iii], who feels that many talented engineers and product designers starting their own companies could have a bigger impact at the larger firms they are flocking away from.

So, if big companies have inherent advantages in scale, expertise, and distribution that make them more capable of capitalizing on innovation, how can we explain the downfall of Blockbuster or Kodak, two companies with market leading positions that missed the opportunity to innovate in their space? It appears the advantage in resources and skills is not enough to ensure innovation.

Some suggest that by acting like start-ups big companies can effectively utilize their strengths to make real, transformative innovation.[iv] That means taking risks, getting passionate talent that can be directed toward a single goal, interacting with the customer more often, and streamlining bureaucracy.

Steve Jobs’ own description of Apple[v] shows that he bought into this theory – that to be innovative companies, regardless of size, need to embrace a culture that encourages innovation. At Apple that culture meant a focused strategy, a willingness to tolerate tension in favor of working together, and instilling a cross-disciplinary view of how the company can succeed. All-told, this strategy hasn’t worked out too poorly for Apple but probably can’t be expected to work or be as easily deployed at other large companies lacking the strong leadership Steve Jobs’ offered.

Jobs’ would have likely agreed with a point made in the Schumpeter column mentioned earlier2; “The key to promoting innovation (and productivity in general) lies in allowing vigorous new companies to grow big, and inefficient old ones to die.”

On the balance, a fair conclusion would be that start-ups do generally embody characteristics that allow innovative ideas to succeed along with an inherently high tolerance for risk but can lack the resources and connections to effectively capitalize on them while bigger firms offer better systems, skills, and distribution channels but can stifle innovation through a reluctance to accept risk and overly-complicated bureaucracy that frustrates entrepreneurs.

Are start-ups more innovative? Only when large companies chose to stifle their ability to make meaningful innovation real.

What is the lesson for the Osmotic Innovator? Structure teams within your organization to value the things that allow innovative ideas to move forward and succeed. Even if the CEO doesn’t value a start-up culture like Steve Jobs you should do your best to encourage the same values in your teams’ innovation efforts.

– Ensure clear focus – make sure the strategy, mission, and customer for your organization is always front and center

– Tolerate tension and argument – people should be willing to speak-up, dissent with listening allows for the best ideas to move forward, product improvements to be made, and builds ownership

– Accept balanced risk –maintain a portfolio of projects that exhibit different degrees of risk, without accepting risk few disruptive or radical ideas will be allocated sufficient resources to succeed

– Give people responsibility – encourage your team to be entrepreneurs that take on leadership and ownership of the ideas they are passionate about

[i] Sam Hogg. Why Small Companies Have the Innovation Advantage. Nov 15, 2011. Entrepeneur. http://www.entrepreneur.com/article/220558

[ii] Big and clever. The Economist. Dec 17, 2011. http://www.economist.com/node/21541826

[iii] Eric Schonfeld. Sean Parker: “Little Startups Are Ridiculously Over-Funded” TechCruch. Nov 15, 2011. http://techcrunch.com/2011/11/15/sean-parker-little-startups-are-ridiculously-overfunded/

[iv] Tomkubilius. 4 Ways Big Companies Can Act Like Start-Ups to be More Innovative. Story of Design by Bright Innovation. March 30, 2011. http://storyofdesign.com/2011/03/30/4-ways-big-companies-can-act-like-start-ups-to-be-more-innovative/

[v] Nilofer Merchant. Apples Startup Culture. Bloomberg Businessweek. June 14, 2010. http://www.businessweek.com/innovate/content/jun2010/id20100610_525759.htm