problems

Observing the Innovators Dilemma

In 1997 Clayton Christensen published The Innovator’s Dilemma: When New Technologies Cause Great Firms to Fail. The book (which we highly recommend) proposed an intriguing explanation as to why large companies with seemingly unlimited resources can fail to see their own demise in the emergence of disruptive technologies. One oft cited example of this phenomenon is the demise of Kodak who not only failed to see the importance of digital photography on their core film business but in fact were the ones who invented digital photography in the first place. The purpose of this post is not to discuss Christensen’s work however but instead to cast our eyes over some industries and see if we can spot companies who might well be in the midst of an innovators dilemma as we type.

In 1997 Clayton Christensen published The Innovator’s Dilemma: When New Technologies Cause Great Firms to Fail. The book (which we highly recommend) proposed an intriguing explanation as to why large companies with seemingly unlimited resources can fail to see their own demise in the emergence of disruptive technologies. One oft cited example of this phenomenon is the demise of Kodak who not only failed to see the importance of digital photography on their core film business but in fact were the ones who invented digital photography in the first place. The purpose of this post is not to discuss Christensen’s work however but instead to cast our eyes over some industries and see if we can spot companies who might well be in the midst of an innovators dilemma as we type.

In order to identify where an innovators dilemma might lie we need to quickly describe the required conditions for its occurrence. A very common approach, and one used by Christensen, is to describe the situation using innovation S-curves as below.

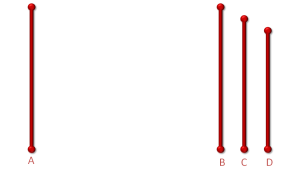

A: A new technology in its infancy. Performance improvements are hard to generate as the innovation is becoming understood. Generally, innovations at this point are only used by very early adopters and the value of the product offering may be limited. B: Rates of performance advances are peaking, rapidly catching up to incumbent technology. The technology becomes commonplace and even the industry standard. New competitor technologies look hobbyist or misaligned. C: The technology matures, performance advances are harder to generate as the limitations of the technology are found. Most people who might use the technology are doing so. New competitor technologies seem to have higher potential and are gaining acceptance. D: The technology fades. People stop using the technology and choose others. A new technology becomes the industry standard. The Dilemma Zone: Technology A is well understood, the industry standard and an integral part of the business model of those employing it. The profitability of the technology is peaking. Technology B looks very promising even to the point where it is the odds on favorite to be the future of the industry; the only question is exactly when.

So, with this set of conditions in mind we will go hunting for some modern dilemmas in the businesses of today. Kodak followed the red S curve to their well-publicized regret, who might be next?

Dilemma #1, HBO: HBO are having a great run at the moment, their internally created content such as Game of Thrones and Boardwalk Empire have generated huge returns for their parent company Time Warner. HBO is one of the most well known and entrenched premium cable channels in the world and its exclusive offerings are an important part of the business model of cable providers such as Verizon and DirecTV. So where is the dilemma? Well, Game of Thrones Season II has been downloaded illegally about 25 million times over the year1 and HBO know why; there is no other way to get it apart from subscribing to a full cable service. HBO could provide downloads through their own site or through iTunes or another vendor but (at least for season 2) chose to take the money i.e. maintained the high premiums from the cable providers at the expense of the pirated copies. Financially this makes sense today but long term HBO may not always have such a gem as Game of Thrones with which to negotiate (or even define) the process of streaming its content on demand.

Dilemma #2, Big Pharma: Big Pharma is REALLY big and is based primarily on a model that is around as old as your granny. Two pillars, small molecule chemistry and blockbuster “one size fits all” treatments are what has driven the growth of this industry since the early 20th century but that is coming to an end. Biotechnology in its many forms is most definitely the future of medicine in the 21st century. A scan of where the breakthrough patents are being generated in the field and you can see the majority are coming out of small Biotechs and Universities not the massive health laboratories of the S&P 500. The problem is that small molecule chemistry (what Big Pharma is great at) is not Biotechnology any more than plumbing is interpretive dance. The initiative needed to transition the capabilities of say, a Pfizer (100,000+ employees2), to a new science is immense, perhaps too immense. Coupled with this is a reality that Biotechnology tends to make very targeted drugs, limiting the opportunity for another “everyone gets a pill” Lipitor or Prosac, a model that Big Pharma now relies on. So the dilemma is set, Big Pharma must re-skill, and possibly re-size, but to do it now or to hold on for just one more blockbuster?

not the massive health laboratories of the S&P 500. The problem is that small molecule chemistry (what Big Pharma is great at) is not Biotechnology any more than plumbing is interpretive dance. The initiative needed to transition the capabilities of say, a Pfizer (100,000+ employees2), to a new science is immense, perhaps too immense. Coupled with this is a reality that Biotechnology tends to make very targeted drugs, limiting the opportunity for another “everyone gets a pill” Lipitor or Prosac, a model that Big Pharma now relies on. So the dilemma is set, Big Pharma must re-skill, and possibly re-size, but to do it now or to hold on for just one more blockbuster?

Dilemma #3, Microsoft Office: Microsoft itself is arguably in the middle of an innovators dilemma but I thought I would pose the case for one of its most profitable jewels, Office being very much in the middle of a technology revolution itself. Office is everywhere, you can’t do business without the ability to open and edit Word, Excel and PowerPoint documents and this has ensured that the Office suite has remained the standard install for companies worldwide for many years. The knock-on effect of Office being the choice of your company is that you are far more likely to install it on your home PC as well, and why learn two different systems? So where is the dilemma? Well, Microsoft knows that it won’t be long before the idea of having to boot up a desktop or notebook to balance the household budget or write your resume will be gone. People will expect to run their households from their tablets and phones while sitting on their sofa not hiding away in the home office. So, Office for tablets? Where is it? The problem is that fully functioning office products are complex, far more complex that we are used to dealing with on tablets and phones. Microsoft’s choices seem to be a) cut back on the functionality (losing their technical advantage), b) teach us a new way of interacting (losing the synergy with the company office) or c) lose the home space all together. You might be thinking that you would still be tied into the Office suite simply because even if you change your home tablet away from Office, other people will still send you Word documents. The simple fact however, is that file type is almost irrelevant these days. Download a free service like Open Office and you will see it is quite capable of opening Word docs and even saving them in Word format so on Monday morning your company PC will be compatible with your weekends endeavor.

Are Schools Killing Creativity?

So far this blog has covered topics mainly focused on how to better enable innovation within your organization. But what if one of the problems you are facing is an educational system that produces people lacking creativity?

So far this blog has covered topics mainly focused on how to better enable innovation within your organization. But what if one of the problems you are facing is an educational system that produces people lacking creativity?

Here is Sir Ken Robinson making the case for re-imagining our educational systems and ultimately how we train people.

Decreasing Conformity in an Innovation Session

If I were to ask you to quickly recall the last session you went to, most likely the first thing you will say is “Well, a group of us got together and…” You will probably then continue to focus on what activities were done, where you went, and the results that were obtained. However, a critically important component is often overlooked – the effect of the group on an individual. Are individuals in a group setting really contributing to the best of their abilities? Yes, we all know there are the introverts and the extroverts, but despite that we still get the best from each person, right? Don’t be so sure.

Consider the Solomon Asch conformity experiment: A straight line was shown to a group of college students who were all in on the experiment except for a single test subject. In the test, a card with a straight line (line A) was shown, followed by a card with another set of lines (lines B,C,D). When asked which line is closest to A, all the students who were part of the experiment were instructed to purposefully give the wrong answer (line C). Because the experiment was preceded by several sets of cards where correct answers were given by the group, and trust established, the test subject was in a position of distress: follow the group or give the correct answer? Over-all, the test subject gave the wrong answer (line C) 32% of the time. During the course of repeating the experiment, about 75% of the time the subject conformed at least once. Only rarely was an individual observed who gave the right answer (line B) each time, while there was a minority (5%) that conformed to the group every time.

Experiments like this one and others that have been conducted in the field of Social Psychology demonstrate “Conformity”. According to Elliot Aronson, author of The Social Animal, conformity is defined as “a change in a persons behaviour or opinions as a result of real or imagined pressure from a person or group of people.” There are several factors that contribute toward conformity, but for simplicity, the main factor to consider is the desire for one to be accepted by his/her group of peers. Considering this, the question for the innovator becomes one of how can we lessen this tendency and encourage more individuality when placed in a group setting?

The answer depends to a large extent on how the innovation session is conducted. There are numerous techniques to engage people and bring out their creativity that are readily found in books, online, and even from professional facilitators. Everything from the colour of the room to specific physical activities has been reviewed at one time. However, one thing not often addressed is how to decrease conformity in a group and nurture an environment where individuals can contribute more to the innovation session.

Ok, so now what? How do we do this you ask? As one may expect, the size of the group has an effect on whether or not someone conforms to the group they are in. As Rod Bond from the University of Sussex[1] describes, a maximum of 3 to 5 people induce this behaviour (with 5 people being where it levels out), while groups of two drastically reduce the effect. This also ties into the next point: having an ally. In a variation of the experiment conducted by Asch as previously described, one of the students acted as an ally to the test subject. Just as before, all the students gave the wrong answer except for one student who was instructed to give the correct answer. In this situation, when the time came for the test subject to provide an answer, the correct one was given. What happened? The pressure to conform was drastically reduced. What does this tell us? Try breaking your large group into smaller groups of two to accomplish a task. Encourage those paired up together to share something funny about themselves. In doing so, you will not only help people create an “ally”, but conformity will have been reduced because you have broken down the larger group.

Some other things you may want to try:

- Break a complex problem down into smaller, more manageable parts. Typically when members of a group are uncertain about a problem, they begin to look to others for confirmation.

- Conduct innovation sessions without the presence of either someone of authority (e.g. Managers or Directors) or an expert in the field that is the focus of the innovation session. This will reduce the tendency of others in the group to look to such figures of authority for approval by agreeing with them.

- Create an activity where members need to make a commitment to their initial judgment, idea, or response. In doing so, their probability to change their mind or conform to the group will greatly decrease.

Why is this important for innovation sessions? Think about it: the Asch experiment drives home that in a typical session, there is a high probability that people will not be giving their own true answer or contribution. By using these techniques, the innovation session facilitator can likely maximize the contribution from each person and hopefully obtain even more ideas and increased levels of creativity.

Resources

Aronson, Elliot. The Social Animal. 10th ed.New York: Worth Publishers, 2008.

Gleitman, Henry, Alan J. Fridlund, and Daniel Reisberg. Psychology. 6th ed.New York: Norton, 2004.

[1] Bond, Rod; Group Process & Intergroup Relations, 2005 Vol 8(4) 331-354

Innovation ownership and the transition

Most product development processes within corporations rely on a regular transition of responsibility as an idea progresses from conceptual to final product. Some of the most common examples are transitions between inventors and feasibility assessment teams, feasibility teams and development teams and even marketing and R&D operations. Often these transitions are also where we see the product development process fail as the product idea never fully takes hold in the imagination of the new team and fades away. One of my preferred ways of

Most product development processes within corporations rely on a regular transition of responsibility as an idea progresses from conceptual to final product. Some of the most common examples are transitions between inventors and feasibility assessment teams, feasibility teams and development teams and even marketing and R&D operations. Often these transitions are also where we see the product development process fail as the product idea never fully takes hold in the imagination of the new team and fades away. One of my preferred ways of  visualizing the issues that can arise during transition is through an analysis of idea “ownership”.

visualizing the issues that can arise during transition is through an analysis of idea “ownership”.

Ownership

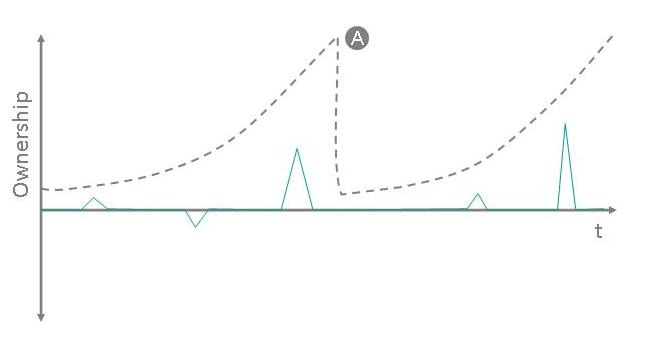

The chart in figure 1 describes the level of ownership that a team developing a particular innovation may experience over time. As the team starts out the commitment level is relatively low, no one has spent much time on the initiative and there are many different paths to success still available to the team. Over time the team feels more commitment towards the innovation path and the sunk cost of the current program of work increases, this increases the ownership of the program.

Complexity expectation

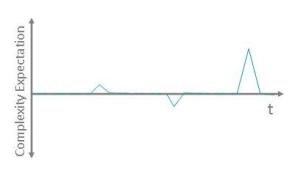

Within every product development project there is a level of complexity that the team is expecting to encounter. This expectation can vary significantly (think landing a man on mars vs. developing a new flavour ice cream) but the important factor is that there is an expectation. Deviations from this expectation are what we call “problems” (or occasionally “lucky breaks”). Tasks that do not deviate from our expectation of complexity are what we call our day job. The chart in figure 2 describes an example of the complexity curve for a project over time.

If we begin to think about how we could measure complexity in the above example it becomes obvious that the level of complexity of a given problem could be measured by the level of commitment and effort required to solve said problem. In essence what we are saying is that every problem we encounter within the product development process will require a particular level of “ownership” in order to be overcome. This allows us to overlay the two previous charts with the common y axis of the theoretical construct “ownership”, see figure 3.

Ownership and the transition

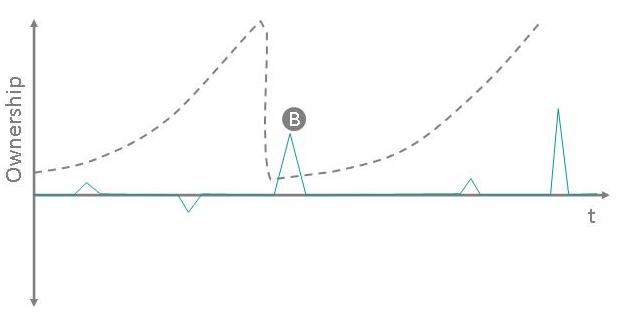

Turning our attention to the concept of ownership as it relates to idea transition between corporate groups we can imagine a (worst case?) scenario where the ownership level of the accepting group post transition is extremely low, Fig 4. This low ownership scenario can arise for many reasons including a lack of understanding of the idea potential, a poor incentive structure (the fabled “not invented here”) or simple housekeeping such as stressed resources limiting the interest in yet another project.

Fundamentally, a project in a low ownership situation is fragile. Problems encountered during this state can cause the project to fail as those responsible for the next development stage see the hurdles as insurmountable, Fig 5. Often these same hurdles are seen in a very different light by those who continue to experience high ownership for the project.

Bridging the gap

How then to avoid issues arising from transition fragility? Obviously one cannot control when an unexpected problem may arise during a project but it is possible to influence ownership in the lead up to, and directly after a responsibility transition. Examples of how this can be achieved are numerous but a couple worth considering include shadowing programs which engage the second group in the decision processes of a project prior to transition, Fig 6. Shadowing programs allow a new transition group to develop understanding and commitment before they take ultimate responsibility for the project.

Another approach uses dovetailed leadership structures which create matrix teams during transition, Fig 7. In this instance a temporary matrix team is formed during transition consisting of the (low ownership) core of the second team reporting into the (high ownership) management of the first team. After a fixed period of time the matrix team is disbanded and reporting lines are reset. This allows for a soft transition where high ownership individuals are always present in the responsible project team.

The innovation transition process within a corporate innovation program can be a very complex procedure in which success is as much down to the personalities of the individuals as the rigor of the systems employed to control it. Companies that focus on solely on the mechanical aspects (document control, handover procedures, technology debriefings etc) may be leaving themselves open to failure through no fault other than the realities of human psychology and the timing of a project hurdle. Innovation programs that incorporate ownership management within their transition processes go a long way to reducing that risk of failure.