Month: March 2012

Can Music and Color Enhance Creativity?

Are you the type of person who listens to their iPod while working? What about when you are at the gym? Is the music different depending upon what you are doing and when? It is often said that music is the soundtrack of our life, and has the ability to make us smile, cry, feel energized, or relaxed. What about color? Are there certain colors you like or dislike?

Are you the type of person who listens to their iPod while working? What about when you are at the gym? Is the music different depending upon what you are doing and when? It is often said that music is the soundtrack of our life, and has the ability to make us smile, cry, feel energized, or relaxed. What about color? Are there certain colors you like or dislike?

Applying this thinking to structuring an innovation session, you might want to find a way to provoke an emotional response. In this post, we will explore how incorporating (or manipulating) our sense of hearing and sight via music and color may assist in enhancing peoples creativity.

All of us have at some point studied the physiology of our eyes and ears. Different frequencies and vibrations in the air reach our eardrum and produce what we term “sound”. Light gets focused, forms an image, and the image is converted to electrical signals that tell the brain of what we “see”. Understanding each of these organs could require extensive study of Anatomy & Physiology and Physics by themselves, but putting the complexity of the human physiology aside, do these senses affect the individual psychologically?

Starting with music, there are numerous papers that examine its impact on intelligence and creativity. You may be aware of the studies regarding pregnant mothers playing classical music and the belief they will have more intelligent children. Although this is still debatable[1], fundamentally it stands that soothing sounds can induce creativity and increase intelligence. What exactly is defined as soothing? According to Dr. Jeffrey Thompson from the Center for Neuroacoustic Research, Delta rhythms of 0.5Hz induct meditative-like states of consciousness and “whenever there are extraordinary meditation states present, brainwave electrical activity between the right/left hemispheres tends to synchronize. This synchronization of the cerebral hemispheres seems to only happen in special circumstances of consciousness – the “aha” state, the moment when the answer to a problem occurs, creative inspiration, great insight, and moments of awareness of ones own existence.”[2] Although a majority of us can not measure the frequency of music we listen to, it is safe to assume that sounds of the harp, Tibetan bowls, recordings of nature, and slow instrumental songs will certainly put us in this required state of mind. It has also been shown that learning how to play an instrument can improve our intelligence and abilities. In a study performed by the Association for Psychological Science, children taking music lessons scored higher on verbal memory tests than a control group without musical training[3]. Although not explored in this blog, it is important to note that music is additionally linked to reducing pain after surgery and is strongly suspected to increase/decrease the violent tendencies of people depending upon the kind of music listened to.

There are many articles and studies explaining how color can enhance mood, productivity, physical performance, and what we purchase (to name but some of the many examples). Several ancient cultures are known to employ what we now term color psychology for healing. Although viewed with scepticism, studies have been conducted that suggest a link between different colors and the state of our mind. One such study performed by the University of British Columbia (UBC) demonstrates how brain performance can be enhanced. According to Juliet Zhu from UBC’s Saunder School of Business, researchers tracked more than 600 participants’ performance on six cognitive tasks that required detail orientation or creativity. Most experiments were conducted on computers, with a screen that was red, blue, or white. As it turns out, red boosted performance on detail oriented tasks such as memory retrieval and proofreading by as much as 31%. When confronted with creative tasks such as brainstorming, blue environmental cues were shown to produce twice as many outputs as compared to the other colours. According to Juliet Zhu, “Thanks to stop signs, emergency vehicles, and teachers red pens, we associate red with danger, mistakes and caution. The avoidance motivation or heightened state that red activates makes us vigilant and thus helps us perform tasks where careful attention is required.” Blue, however, encourages us to think outside the box and be creative she says. “Through associations with the sky, the ocean and water, most people associate blue with openness, peace, and tranquillity. The benign cues make people feel safe about being creative and exploratory.”[4] Other colors are also believed to affect the body and mind in certain ways – just do a quick Google search and you will be amazed at the abundance of information on both the positive and negative aspects assigned to each one.

For the Osmotic Innovator, this information is yet another technique to add to the growing toolbox of ways to bring out creativity in people during innovation sessions. Some examples include:

- Keep people creative and energetic by alternating between classical and dance music. Use the classical music when you need them to be focused and creative. When needed, inject energy into the room by playing something with a faster beat.

- Place the challenge statement on a blue background and hang it up so everyone can see

- Play with the emotions different colors can evoke by use of colored lighting, and/or making available colored paper, crayons, and pens. Have no “traditional” white paper available.

- Form teams and force each one to be immersed in a particular color as they innovate (have them wear that color shirt or other type of clothing and use supplies of only that color). Allow the groups to experience being immersed in different colors.

- Do the same thing as described in the previous suggestion, but with the addition of music. Maybe subject one group to Jazz, another to Classical, and another to Dance/Rock.

These are just a few examples of what could be done to improve creativity. Experiment the incorporation of music and color with your own sessions and see what happens.

Osmotic Innovation is Linking You Up

The Five Personalities of Innovators

According to this article by Brenna Sniderman published on Forbes.com the most successful teams include all five personality types. Click through to read about Movers and Shakers, Hangers-on, Experimenters, Star Pupils, and Controllers. Which are you and which are missing from your team?

Is Working for a Corporation Better?

The team at Fast Company gives 9 reasons you should work at a corporate job rather than a start-up. We’ll let the author, Jeetu Patel, sum it up; “Startups can be amazing places to work, and the euphoria surrounding them has a high degree of contagion. But future leaders have unique lessons to learn by working for larger, more established companies as well.”

In previous blogs, we have explored the topic of groups and interactions among people and have described the drawbacks as well as importance of including people from outside a specific type of organization. In this article, Jose Baldaia provides an argument on the importance of a team and the power of the contributions it can provide to a company.

The Trap of the Knowledge Economy

We take it for granted that we live in a world of data. Google and Facebook both rely on user data to drive their innovation and products while constantly creating new ways to collect and use that data. Facebook is a great example: “[it] has some 750 million users, half of whom log in every day. The average user has 130 friends and spends about 60 minutes a day tinkering on the network.”[1] Thanks to programs that allow them to monitor your every click the company is able to understand its consumer to an extent never before seen. In fact, it is now sometimes said that ‘Every second of every day, more data is being created than our minds can possibly process.’[2]

We take it for granted that we live in a world of data. Google and Facebook both rely on user data to drive their innovation and products while constantly creating new ways to collect and use that data. Facebook is a great example: “[it] has some 750 million users, half of whom log in every day. The average user has 130 friends and spends about 60 minutes a day tinkering on the network.”[1] Thanks to programs that allow them to monitor your every click the company is able to understand its consumer to an extent never before seen. In fact, it is now sometimes said that ‘Every second of every day, more data is being created than our minds can possibly process.’[2]

This new paradigm, what some term the ‘knowledge economy’, has spread into every industry and has quickly become a standard factor in internal product and innovation evaluations. We now have a wealth of information about our consumers that we can use for good . . . or bad. As well, consumers now know far more than they ever have before. For the Osmotic Innovator, it is important to understand how this happened and how it has impacted the way we should go about innovation.

In reviewing the impact of the knowledge economy on product development and innovation we don’t need to go to far into the past to find a time when data was not so easily obtained yet product development was undergoing a renaissance. At the turn of the century, after the industrial revolution had changed both the way consumers lived and companies grew, people like Ford and Edison made fortunes inventing new products that have since become iconic. But for every Ford and Edison success there were many failures – like Edisons’ automatic vote-tally system for Congress[3] – or a failed inventor whose radical ideas never were embraced in their time (think about Tesla). The number of failed innovations during this time period was enormous, just as some of the successes (the Model T and the Light bulb) were equally enormous. Without access to data, companies and inventors trusted their gut, valuing passion for a product as the driving force in creating and launching into the market.

Moving forward to the 1950’s & 1960’s one enters another golden age in product development in Western economies – the age of marketing. If you’ve ever watched an episode of Mad Men you know the stereotypes: bold marketers using data (and their intuition) to make new products successful by attempting to actually understand and meet new consumer needs. With a market already satiated by 50 years of new products and innovation, companies saw segmentation of markets and use of data to identify the best and safest product launches as one way to obtain a competitive advantage. Data was available and used, but it wasn’t the primary driving factor in innovation. Did this increase the number of product successes or the ratio of product success versus failure? We know that product launch success was actually higher in the 1950’s than now, but don’t have the data to understand how this stacks up against earlier periods.[4]

Fast forward 50 more years to present day – the era of the ‘knowledge economy’. Vast improvements in computing have allowed equivalent improvements in analysis and theory. No product is launched by a large company without extensive vetting through any number of market research toolkits and analytical systems. Consumers are split into segments and dissected in every way possible as companies in mature and developed industries look for any possible unmet need. Disruptive products that don’t fit the models are scrapped while incremental innovations are launched because they are able to fit into the segments that have been so carefully developed. In many ways, the innovator in a large firm is now crushed by the weight of the data available to them instead of empowered. With all of this data in hand guiding decisions for large firms we must have achieved a new high in new product launch success, right? Actually, current measures show that only 1/3 of NPD launches are ‘successful’[5] – and the consensus is that this number that has actually decreased since the 1950’s. Obviously, the exponential increases in data and advances in market research tools are not returning an equivalent value in NPD success.

Fast forward 50 more years to present day – the era of the ‘knowledge economy’. Vast improvements in computing have allowed equivalent improvements in analysis and theory. No product is launched by a large company without extensive vetting through any number of market research toolkits and analytical systems. Consumers are split into segments and dissected in every way possible as companies in mature and developed industries look for any possible unmet need. Disruptive products that don’t fit the models are scrapped while incremental innovations are launched because they are able to fit into the segments that have been so carefully developed. In many ways, the innovator in a large firm is now crushed by the weight of the data available to them instead of empowered. With all of this data in hand guiding decisions for large firms we must have achieved a new high in new product launch success, right? Actually, current measures show that only 1/3 of NPD launches are ‘successful’[5] – and the consensus is that this number that has actually decreased since the 1950’s. Obviously, the exponential increases in data and advances in market research tools are not returning an equivalent value in NPD success.

One might argue that only companies ignoring the market research ‘facts’ are launching disruptive new products – the ones that actually capture real substantial value and create new markets. Take it from Steve Jobs, praised universally for being a disruptive thinker and innovator: “When asked what market research went into the iPad, Jobs replied: “None. It’s not the consumers’ job to know what they want…we figure out what we want. And I think we’re pretty good at having the right discipline think through whether a lot of other people are going to want it, too.””[6]

The figure below shows the growth of the ‘knowledge economy’, the corresponding drop in the capacity of a large company to launch disruptive or truly innovative products, and relative product launch success rates. Unless your company is willing to ignore conventional market research and analytical tools – which some might call wilfully ignoring your consumer – delivering true innovation to the market is nearly impossible. That is why disruptive innovation seems to come from smaller companies and start-ups; without a business to protect and with few resources, market research is an unnecessary luxury.

Looking at the discussion graphically – the question to ask is why are companies so reliant on data and market research when using it encourages incremental innovation without improving new product launch success? This is the trap of the knowledge economy: it promises to remove risk from new product development yet prevents the innovator from truly exploring disruptive innovation that could create new markets.

How can the Osmotic Innovator avoid falling into the trap of the knowledge economy?

- don’t make every product fit the models currently used by your company

- be willing to trust your organizations understanding of what the consumer will want (just like Steve Jobs)

- be bold in launching risky products in the face of failure – most ‘safe’ products fail anyways

Are these prescription alone enough to solve the problem of low NPD launch success rates or change the reliance of mature companies on data? No. But they should give the Osmotic Innovator something to consider the next time you are working through the portfolio.

Innovative or Not: The Toyota Prius

Every so often we plan to take a look at a new or iconic product to evaluate the innovation (or lack thereof) behind it. One of us will argue for good, one for bad, and the third will make a final judgement.

Every so often we plan to take a look at a new or iconic product to evaluate the innovation (or lack thereof) behind it. One of us will argue for good, one for bad, and the third will make a final judgement.

Have a suggestion for what we should do next or disagree with our assessments? Have your say in the comments.

This week the Toyota Prius comes under our microscope:

Not Innovative: The Prius is a car that inspires some strong reactions – none of which should be an exclamation of ‘Its So Innovative!’ As one of the first efforts by a major car maker to bring hybrid technology to the mainstream the Prius has slowly achieved commercial success and cult status without doing anything innovative. When it was first launched the Cato Institute had this to say regarding the Prius; “With most subsidies, the government pays someone to produce something that no one wants to buy. But what happens when the government pays people to buy something that no one wants to produce?” and “News stories about the popularity of these vehicles simply aren’t true. There’s a waiting list … but that’s because Toyota will only ship 12,000.” In fact, for the first six years the Prius never sold more than 50,000 units in a year – even with extensive tax subsidies!

Not Innovative: The Prius is a car that inspires some strong reactions – none of which should be an exclamation of ‘Its So Innovative!’ As one of the first efforts by a major car maker to bring hybrid technology to the mainstream the Prius has slowly achieved commercial success and cult status without doing anything innovative. When it was first launched the Cato Institute had this to say regarding the Prius; “With most subsidies, the government pays someone to produce something that no one wants to buy. But what happens when the government pays people to buy something that no one wants to produce?” and “News stories about the popularity of these vehicles simply aren’t true. There’s a waiting list … but that’s because Toyota will only ship 12,000.” In fact, for the first six years the Prius never sold more than 50,000 units in a year – even with extensive tax subsidies!

The technology used in the Prius isn’t anything unique or disruptive – it’s the same as that used in any number of hybrids on the market. And it certainly wasn’t the first hybrid car, with the brake regeneration technology based on an invention from the 1970’s. The Prius is a success not because it was innovative – it is a success because it became an emblem of the environmental movement. With the help of generous government subsidies and marketing the Prius was able to overcome high cost and limited consumer interest to become the kind of ‘innovation’ deservedly mocked by South Park.

Innovative: There are two types of people in this world, those whose car says something about them personally and those who drive Honda Accords. Originally it was the ad men who told us what our cars stood for, and the Accord guys loved pointing out how much they were ignoring them…until the Prius.

Innovative: There are two types of people in this world, those whose car says something about them personally and those who drive Honda Accords. Originally it was the ad men who told us what our cars stood for, and the Accord guys loved pointing out how much they were ignoring them…until the Prius.

Is the Prius innovative? Of course it is, but not because it is a hybrid (there are  plenty of those) and not because it is the most successful (although it is). The Prius is an innovative car because it created a new personal statement that a driver could wear on the road. The Prius says as much about its driver as an F250 with a gun rack and Playboy mud flaps. The Prius was designed as a hybrid; you don’t have to look for the badge on the back to see if that Prius quietly gliding past you is a hybrid because they are ALL hybrids, its shape makes that statement, unlike its competitors. The Prius was the innovation that changed everything. Suddenly at wine tasting’s all over the suburbs the Accord drivers’ smug indifference to the might of Madison Avenue could be trumped by the simple statement “of course Steve and I went for the Prius”. The middle class was rocked to its core and the malls would never be the same again. A sports car says you are dangerous, a luxury car says you have made it and a Prius is the conspicuous consumption of politics.

plenty of those) and not because it is the most successful (although it is). The Prius is an innovative car because it created a new personal statement that a driver could wear on the road. The Prius says as much about its driver as an F250 with a gun rack and Playboy mud flaps. The Prius was designed as a hybrid; you don’t have to look for the badge on the back to see if that Prius quietly gliding past you is a hybrid because they are ALL hybrids, its shape makes that statement, unlike its competitors. The Prius was the innovation that changed everything. Suddenly at wine tasting’s all over the suburbs the Accord drivers’ smug indifference to the might of Madison Avenue could be trumped by the simple statement “of course Steve and I went for the Prius”. The middle class was rocked to its core and the malls would never be the same again. A sports car says you are dangerous, a luxury car says you have made it and a Prius is the conspicuous consumption of politics.

Judgement: Not Innovative! Although the Prius has a different shape from its competitors, this feature alone is certainly not enough to consider it innovative. There are many products that differentiate themselves from competitors via shape and colour, but fundamentally offer nothing new or unique. As mentioned, the technology is the same as used by other hybrid manufacturers and it certainly wasn’t the first to lead the way for others to follow. In fact, a quick Google search reveals that back in 1870, Sir David Salomon developed a car with a light electric motor and very heavy storage batteries[1]. As for its being embraced by consumers as a political statement; such statements bear no merit toward a reflection on the level of innovation for a product. Consumers are known to embrace random products to either make a statement about or flock ‘en mass’ to madly purchase. In 1975 consumers went crazy for what was called the Pet Rock, earning its “creator” over 15 million dollars! So even with its differentiated design and being considered the “conspicuous consumption of politics”, the Prius is still far from being innovative.

Judgement: Not Innovative! Although the Prius has a different shape from its competitors, this feature alone is certainly not enough to consider it innovative. There are many products that differentiate themselves from competitors via shape and colour, but fundamentally offer nothing new or unique. As mentioned, the technology is the same as used by other hybrid manufacturers and it certainly wasn’t the first to lead the way for others to follow. In fact, a quick Google search reveals that back in 1870, Sir David Salomon developed a car with a light electric motor and very heavy storage batteries[1]. As for its being embraced by consumers as a political statement; such statements bear no merit toward a reflection on the level of innovation for a product. Consumers are known to embrace random products to either make a statement about or flock ‘en mass’ to madly purchase. In 1975 consumers went crazy for what was called the Pet Rock, earning its “creator” over 15 million dollars! So even with its differentiated design and being considered the “conspicuous consumption of politics”, the Prius is still far from being innovative.

Motivation and Rewards: The Application to Innovation

We live in a corporate environment where time is scarce and employees are trying to balance their career and outside interests (e.g. family, personal hobbies, health, etc). Because of this, most people simply go to their job and don’t really want to participate in any innovation sessions or activities that may require time above and beyond what is required. They view innovation as yet another objective added to the already long list of whats expected of them in their daily work routine. One way companies address approaches to innovation, is by conducting innovation sessions. Most likely innovation sessions have participants from the company who get together and through use of a facilitator, perform different activities to generate ideas.

We live in a corporate environment where time is scarce and employees are trying to balance their career and outside interests (e.g. family, personal hobbies, health, etc). Because of this, most people simply go to their job and don’t really want to participate in any innovation sessions or activities that may require time above and beyond what is required. They view innovation as yet another objective added to the already long list of whats expected of them in their daily work routine. One way companies address approaches to innovation, is by conducting innovation sessions. Most likely innovation sessions have participants from the company who get together and through use of a facilitator, perform different activities to generate ideas.

In a perfect world, every employee within a company would be excited to attend such a session, and would be full of ideas. However, the reality is companies tend to invite people regardless of their interest or abilities, and so as a result, we have to deal with people who are not engaged, not innovative, or have simply been invited because they funded the event. How can we then motivate those who are not engaged in the innovation session and don’t particularly care to be there?

Typically innovation sessions have reward(s) planned at certain stages when either a team or individual completes some milestone or is perceived to be a large contributor of ideas. Why? Well, many (if not all) of us at some time or another received an incentive to complete a task. Therefore, it is only logical that everyone will be motivated to be innovative if there was a reward, right?

Although there is evidence to support that rewarding certain behavior each time it is observed will increase the frequency of that behavior, this is a very general conclusion and does not take into account peoples internal thoughts about themselves, their self-perspective, and motivation to behave in a certain way. Generally, motivation can be either intrinsic or extrinsic. Intrinsic motivations are those that arise from within – doing something because you want to – while extrinsic motivations mean people are seeking a reward, such as money, a good grade in class, or a trophy at a sporting event[1]. According to self-perception theory (SPT), replacing intrinsic motivation with extrinsic motivation may actually make people enjoy the activity less or loose interest altogether. This is due to what has been termed the overjustification effect, which results when people begin to view their behavior as being caused by rewards instead of realizing the extent intrinsic motivation actually played. Psychologist Daryl Bem, developer of SPT, conducted an experiment where subjects listened to a tape of a man enthusiastically describing a tedious peg-turning task. Some of the subjects were informed the man was paid $20 for his testimonial while another group was told he was paid $1. Those who were in the group informed that the man was only paid $1 felt as though he must have thoroughly enjoyed the task. This is in contrast with the other group who felt the exact opposite.

Considering motivation from the Industrial-Organizational (I-O) Psychology approach, it becomes something a bit complex, but at the same time provides some valuable insight into how we can motivate and engage more employees in innovation – which is the ultimate goal for the Osmotic Innovator. Maslows Hierarchy of Needs essentially states we have different levels of needs that must be sequentially fulfilled before we can reach self actualization (the desire of a person to develop their capacities to the fullest). Although this has become the most popular way to think about motivation, there has been little research performed to test this theory, and the research that has been performed is not completely supportive. There soon emerged a new approach to understand motivation and with this came Vrooms VIE Theory which was placed into a new category termed “Person-As-Godlike: The Scientist Model”. Using Maslows Hierarchy of Needs as a base, VIE (Valence, Instrumentality, Expectancy) theory provides a definition for each component. Valence identifies how psychological objects in an environment have an attracting and repelling force. For example, most would find money attracting and uninteresting work as repelling. Instrumentality deals with the relationship between performance and expected outcomes. An example provided by Frank J. Landy and Jeffrey M. Conte is that of a promotion. Usually a promotion means a higher salary and more prestige, but it may also include more responsibility and longer hours. Once a person is aware of these instrumentalities (essentially Pros and Cons), they can better decide which outcome is better. Lastly, expectancy is defined through this theory as the individuals belief that increased effort leads to successful performance.

Now that we have explored all the technical theories and provided a bit more information from Psychology, what does it mean for the Osmotic Innovator? Excluding the unexplored link between emotion and motivation, we can extrapolate the following:

- Inform employees what benefits may arise from their increased innovation. Explain how things like increased company exposure and the ability to work on their own project all may stem from an increasingly innovative environment.

- Let employees know what an expected outcome would be from an action they begin to perform. In other words, have them consider how increased thinking and participation in innovative programs may ultimately lead to things they want – directly or indirectly (e.g. bonuses, opportunities for promotion, etc)

- Provide small incremental incentives during innovation sessions to those who are perceived to be completely unmotivated. It has been shown that providing incentives to those who completely lack the intrinsic motivation for something can not hurt – it can only potentially help for the duration of the event.

- Know your audience. Begin to meet with those who seem to be lacking motivation and talk to them. You will be amazed at what information you can gain and leverage to get them motivated. Highlight how any contributions they make toward promoting a better innovative environment is valued. Maybe even make them in charge of proposing (and possibly implementing) how a more innovative and positive work environment can be accomplished.

These are just a few suggestions that can be quickly and easily tried by any organization. Remember, motivation is a complex topic and there is really no “one size fits all” approach. Even today, there are debates within the Psychology community regarding the validity of some motivational theories. Hopefully by implementing some of the suggestions above (and maybe even coming up with a few of your own), the innovative culture can begin to become infectious and slowly have a positive effect on everyone around.

References

Levy, Paul E. Industrial Organizational Psychology. 3rd Ed. New York: Worth Publishers, 2009.

Landy, F. J. & Conte, M. Work in the 21st Century: An Introduction to Industrial and Organizational Psychology. 2nd Ed. Malden, Ma.: Blackwell Publishing, 2007.

Aronson, Elliot, Timothy D. Wilson, and Robin M. Akert. Social Psychology. 7th Ed. NJ: Prentice Hall, 2010.

Myers, David G. Social Psychology. 10th Ed. McGraw Hill, 2009

Aronson, Elliot. The Social Animal. 10th Ed. New York: Worth Publishers, 2008.

[1] Researchnews.osu.edu/archive/inmotiv.htm

Innovative or Not: Google

Every so often we plan to take a look at a new or iconic product to evaluate the innovation (or lack thereof) behind it. One of us will argue for good, one for bad, and the third will make a final judgement.

Every so often we plan to take a look at a new or iconic product to evaluate the innovation (or lack thereof) behind it. One of us will argue for good, one for bad, and the third will make a final judgement.

Have a suggestion for what we should do next or disagree with our assessments? Have your say in the comments.

This week Google Search comes under our microscope:

Not Innovative: When someone tells you to look something up on the internet, you will most likely hear the phrase “Google it”. Asking a Google user to try another search engine almost makes a person feel uncomfortable. Although cited in numerous articles as being one of the most innovative companies today, was this search engine really innovative when it first started? Back in 1998 (when Google went public) some of the top search engines used were AltaVista, MSN Search, and Yahoo!. AltaVista used a fast multi-threaded crawler termed Scooter which covered numerous web pages and received 13 million queries per day. It was a huge success and was earning millions within a few years of its launch. Another powerful search engine at the time, Yahoo!, organized websites in a hierarchy as opposed to a searchable index of pages. Yahoo! grew quickly along with its stock price. Google emerged during this time with its own variation that returns based on priority ranking and offered Boolean operators for an option for customization. Considering all the available search engines, and the power they had – returning web pages matching what a person looks for – why would one be considered more innovative than any other? Although most utilized the same technology, some (like Yahoo!) were different and offered something unique. Therefore if we were to consider the whole search engine landscape during this time, singling out Google as emerging with something more innovative than any other search engine is a rather difficult task to do.

Not Innovative: When someone tells you to look something up on the internet, you will most likely hear the phrase “Google it”. Asking a Google user to try another search engine almost makes a person feel uncomfortable. Although cited in numerous articles as being one of the most innovative companies today, was this search engine really innovative when it first started? Back in 1998 (when Google went public) some of the top search engines used were AltaVista, MSN Search, and Yahoo!. AltaVista used a fast multi-threaded crawler termed Scooter which covered numerous web pages and received 13 million queries per day. It was a huge success and was earning millions within a few years of its launch. Another powerful search engine at the time, Yahoo!, organized websites in a hierarchy as opposed to a searchable index of pages. Yahoo! grew quickly along with its stock price. Google emerged during this time with its own variation that returns based on priority ranking and offered Boolean operators for an option for customization. Considering all the available search engines, and the power they had – returning web pages matching what a person looks for – why would one be considered more innovative than any other? Although most utilized the same technology, some (like Yahoo!) were different and offered something unique. Therefore if we were to consider the whole search engine landscape during this time, singling out Google as emerging with something more innovative than any other search engine is a rather difficult task to do.

Innovative: Google‘s main innovation was in ranking pages in a way that consistently returned higher quality results than the status quo. This forced every other search engine to change their foundational algorithms. In other words, it drastically disrupted the entire business of searching the internet; it’s the very definition of a disruptive innovation.

Innovative: Google‘s main innovation was in ranking pages in a way that consistently returned higher quality results than the status quo. This forced every other search engine to change their foundational algorithms. In other words, it drastically disrupted the entire business of searching the internet; it’s the very definition of a disruptive innovation.

When Google began in early 1996, search engines still ranked results by an algorithm that counted how frequently search terms appeared on a page, and returned whatever page mentioned your search terms the most. Today, we know this system is easily tricked and returns low quality results. Google’s innovation was called “PageRank”, a system that ranked pages by how often other pages linked to it. Google treated every link to a page as a “vote” for that page, thus making the internet into a sort of democracy. Also, when a page had lots of votes, its votes carried more weight, refining the system to be smarter and harder to trick.

When Google began in early 1996, search engines still ranked results by an algorithm that counted how frequently search terms appeared on a page, and returned whatever page mentioned your search terms the most. Today, we know this system is easily tricked and returns low quality results. Google’s innovation was called “PageRank”, a system that ranked pages by how often other pages linked to it. Google treated every link to a page as a “vote” for that page, thus making the internet into a sort of democracy. Also, when a page had lots of votes, its votes carried more weight, refining the system to be smarter and harder to trick.

Google went further though: their page worked faster than anyone else’s. By building their unique homepage to be blank, except a search box, it loaded almost instantly. In addition, their advertisements were text only, carrying the two-fold benefit of loading faster and being less annoying.

Google’s website offered a faster service that returned higher quality results, all based on a system in which people decided which websites were most useful. Google didn’t just make a better, innovative search engine, they made the internet more democratic.

Judgement: Innovative! The definition of disruptive innovation is using existing technology to deliver what may appear to be an inferior product that meets the core needs of new and emerging market segments. When it first launched, Google, with its stripped down front page may have seemed lacking in comparison to existing (and successful) search engines like Yahoo! and Webcrawler. However, Google was actually disrupting search by identifying the core need of consumers – fast and relevant search results. Was this a radical innovation, incorporating new technology to outpace its competitors? No. But it was a massively successful example of disruptive innovation, transforming an industry by applying known technology in a new way. Doing search (and only search) very well allowed Google to become synonymous with the internet usage and to grow its business into all of its current segments.

Judgement: Innovative! The definition of disruptive innovation is using existing technology to deliver what may appear to be an inferior product that meets the core needs of new and emerging market segments. When it first launched, Google, with its stripped down front page may have seemed lacking in comparison to existing (and successful) search engines like Yahoo! and Webcrawler. However, Google was actually disrupting search by identifying the core need of consumers – fast and relevant search results. Was this a radical innovation, incorporating new technology to outpace its competitors? No. But it was a massively successful example of disruptive innovation, transforming an industry by applying known technology in a new way. Doing search (and only search) very well allowed Google to become synonymous with the internet usage and to grow its business into all of its current segments.

Telling the Company Secrets – Defensive Publishing Pt. 2.

Over the past few decades many corporations have seen exponential increases in costs associated with their IP portfolio and an increased drain on technical resource to support a “patent everything we invent” approach. Increasingly defensive publishing is being accepted by more industries and is becoming commonplace in companies where IP and the costs associated with it were once of little concern. In the first post of this two part series we examined routes for defensive publication, here we will discuss how defensive publishing can replace several common patenting strategies: cost limitation, picket fencing, freedom to practice, trade secrets, and patent races.

Over the past few decades many corporations have seen exponential increases in costs associated with their IP portfolio and an increased drain on technical resource to support a “patent everything we invent” approach. Increasingly defensive publishing is being accepted by more industries and is becoming commonplace in companies where IP and the costs associated with it were once of little concern. In the first post of this two part series we examined routes for defensive publication, here we will discuss how defensive publishing can replace several common patenting strategies: cost limitation, picket fencing, freedom to practice, trade secrets, and patent races.

Cost limitation

Perhaps the most common reason for companies to choose defensive publishing strategies over blanket patent tactics is to limit the cost of maintaining the portfolio. By simply defining inventions into either core patents and supporting IP many companies can offset their legal costs significantly while at the same time having limited if any effect on the overall strength of their patent portfolio. For a company utilizing a defensive publishing strategy the supporting or fringe IP could be published in trade journals or commercial publications to protect against competitor ownership while limiting cost of maintaining the real patent portfolio.

Picket fence

Picket fencing or mine-fielding is the process of filing variant patents around a central patent core. When executed properly, the picket fence creates a high barrier to entry for competitors and greatly restricts their ability to practice in spaces adjacent to the core inventions. In most cases the picket fence patents are of much weaker quality and, if the central patent is well-executed, have limited value  unless there is the intent to produce the invention described in the patent or if the picket patent can be delivered independent of the central patent claims.

unless there is the intent to produce the invention described in the patent or if the picket patent can be delivered independent of the central patent claims.

Defensive publishing alternatives to picket fencing practices follow the same systems as cost limitation strategies where possible inventions are described as either core or peripheral. Peripheral inventions are then published into the public domain, preferably in an easily searchable database and even more preferably in a publication likely to be discovered within a patent office examiners search report. The point of picket fencing is primarily as a deterrent and so public domain disclosure in hidden or obscure publication routes is of limited use within a defensive framework.

Freedom to practice

Often corporations will make their profit, not by inventing something new, but by taking a fringe or known products mainstream. But what happens when that fringe product is really really fringe? Consider this scenario; Company A discovers an unpatented widget on sale in Korea they believe it has the potential to be a blockbuster product in the USA. They begin developing the product for a US launch, modifying the designs, building manufacturing capability and planning the marketing strategy. An IP screen late in the process identifies a recently published patent from Competitor B which describes the popular widget and claims ownership of the invention. How can this be? The product has been on sale in Korea FOR YEARS! Over the next few months Company A rallies their legal department to plan their defense. A supply director delays approving a production line until “after the legal issues have been resolved” and the feeling from the business as a whole is frustration.

Fundamentally the patent system isn’t broken, Competitor B’s claim over the invention is void and eventually will be rescinded but the time and cost to Company A is significant and real. In this case had Company A employed a defensive publishing strategy known as prior art elucidation they could have avoided the frustrating scenario outlined above. Given the emergence of ‘patent trolls’ and likely presence of an aggressively patenting competitor in any industry using defensive publishing to ensure freedom to practice can be very important.

The cause of (and solution to) this scenario lies within the patent office who cannot possibly be aware of all prior art and so often will grant patents on inventions that are within the public domain. Ensuring freedom to practice by disclosing the prior art into easily found and searched publications is one way of improving the chance of any future competitor filings being rejected and thus limiting the potential defensive cost. The most suitable although not the most common approach is to utilize commercial publications for the prior art elucidation. Companies such as ResearchDisclosure.com are very well suited to prior art elucidation due to their agreements with IPO member states which improve the chance of the information being found during the search process.

Patent races

The use of defensive publishing within the context of a patent race is an interesting strategy. Basically the approach allows a company to decide how it wishes to compete, on first to patent terms or on first to market terms. The scenario of a patent race between corporations occurs when a common technology goal is defined and the experimental path to the goal is well-defined. In this instance the companies developing the technology are making an all in bet. Only one company is likely to succeed and the loser is likely to face significant setbacks to its development capacity. By applying a defensive publishing strategy that pushes non-core inventions into the public domain rather than building a patent case the company can get a better return on its research investment and give itself a better chance at winning its all-in bet. Taken to the logical conclusion a company may even choose to publish everything it discovers, as is discovers it, in an attempt to remove any chance of a competitor ultimately owning a strong patent in the field. In this case the company is banking on a level playing field being a better competitive option than the chance of winning the all-in bet.

The use of defensive publishing within the context of a patent race is an interesting strategy. Basically the approach allows a company to decide how it wishes to compete, on first to patent terms or on first to market terms. The scenario of a patent race between corporations occurs when a common technology goal is defined and the experimental path to the goal is well-defined. In this instance the companies developing the technology are making an all in bet. Only one company is likely to succeed and the loser is likely to face significant setbacks to its development capacity. By applying a defensive publishing strategy that pushes non-core inventions into the public domain rather than building a patent case the company can get a better return on its research investment and give itself a better chance at winning its all-in bet. Taken to the logical conclusion a company may even choose to publish everything it discovers, as is discovers it, in an attempt to remove any chance of a competitor ultimately owning a strong patent in the field. In this case the company is banking on a level playing field being a better competitive option than the chance of winning the all-in bet.

Unenforceable trade secrets

The use of patents to protect IP that was traditionally kept as trade secrets has increased over the past few decades. This is possibly due to the mobile nature of the modern workforce and internet publishing making trade secrets almost impossible to keep. This trend however has given rise to the problem of the unenforceable trade secret patent. Usually this situation arises when a novel process is patented by a company but the patented process produces an indistinguishable product from the prior art. In this case the patent is close to useless and in the worst case gives away any competitive advantage that the technology advance had generated. The system for defending trade secrets however results in one piece of litigation risk that can be avoided through the use of defensive publishing demonstrated by the following scenario; Engineers at Company A develop a novel processing technique to make their widget at half the cost of the old process. The process leaves no fingerprint other than on the accounts department i.e. the new widget is indistinguishable from the old widget. The lawyers at Company A rationalize that to patent the new process would be of less value to the company than to keep it a trade secret and steps are put in place to maintain this. Five years later a patent on a widget making process is published from Competitor B. The lawyers advise that Company B’s process is substantially the same as Company A’s and that they should prepare some sort of legal defense to ensure that production can continue if a legal challenge were to come about.

Fundamentally, the trade secret process is not flawed, Competitor B’s claim over a process that has been used by Company A for years is void, but the cost of defending a process they have always used is real and annoying. In this case the use of a defensive publishing strategy known as hidden disclosure may have advantages.

Methods for creating hidden disclosure are quite varied but essentially the approach is to place the trade secret into the public domain in a manner that, while being entered into the record as a matter of fact, does not create enough interest or is not accessible to enough people to fully surrender the invention. Methods that achieve this include using the procedures of the patent system itself (withdrawn patents etc) and the use of non industry publications. Maybe even the local classifieds could be a sufficient enough publication to cause a competitor to drop a costly lawsuit?

Osmotic Innovation is Linking You Up

Top Tips for Building an Innovation Culture

This is at the heart of what we are talking about with OI.

Motley Fool Money talks Innovation

If you aren’t a subscriber to the always entertaining Money radio show podcast you should be, but you have to listen when they talk innovation with Dartmouth College Professor of Business Ron Adner, author of The Wide Lens: A New Strategy for Innovation in the Feb 24, 2012 show.

How Innovation Becomes Infectious

As Osmotic Innovators, we want innovation to become something that spreads throughout an organization. Here, Jeffrey Phillips compares an innovative organization to a virus that our “body” (think corporate culture) accepts.

An Enlightened IP Strategy for the Osmotic Innovator

In the last week we’ve discussed using Defensive Publications as a strategy to reduce the overhead associated with patent filings. However, we’ve never really given a detailed explanation of how this concept fits in an over-all intellectual property (IP) strategy for an innovating organization.

In the last week we’ve discussed using Defensive Publications as a strategy to reduce the overhead associated with patent filings. However, we’ve never really given a detailed explanation of how this concept fits in an over-all intellectual property (IP) strategy for an innovating organization.

Often, in the excitement of creating new products from an innovation or invention the tendency is to rush directly from idea / proof of principle to the lawyers’ office to begin drafting patents. Why is it so ingrained in a corporation to patent any new idea or process? Perhaps for some it is because patents can be used as a measure of R&D productivity, effort, or inventiveness. Patents also offer a chance for recognition for inventors and the company amongst their peers. Finally, those responsible can find comfort in the fact that the organizations interests are protected from competition. However, as expressed in the prior posts patents can be an expensive way to protect intellectual property – besides the obvious cost of filing the documents across the globe the organization must also consider the financial cost over time to maintain the portfolio, the value of the time the legal department will spend managing the portfolio, and the impact on R&D productivity as resources are directed to fulfil the data and testing requirements (often outside of the focus of any related project). The filing fees for a patent can pale in comparison to the loss in productivity and resources that might be incurred by a simple patent filing. For resource constrained companies a better process is needed.

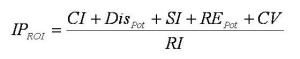

The figure above shows the process that might be used by enlightened organizations to manage the intellectual property strategy process. Rather than rushing from idea to patent, as often occurs, the identification of a new idea or innovation should lead to a strategic discussion. During that discussion a number of criteria might be used to evaluate the idea, leading to several possible outcomes.

The primary criteria that would be best utilized to direct the decision include:

- Competitive Intensity (CI): the position of the organization in the market and in relation to its competitors, as well as market pressure, can dictate to a large extent the need to protect or the possibility of using a less resource intensive mechanism. In highly competitive spaces patenting may well be the best path forward, in spaces where a company has market leadership with few threats, disclosure (keeping the playing field level) may well be sufficient.

- Disruptive Potential (DisPot): the likelihood of the innovation to transform the market or industry should also be taken into account. Disruptions creating new consumer benefits should be viewed differently than innovations that benefit only the company. For example, for a company that has a market leading position due to brand or scale an innovation allowing cheaper product manufacture may not require patent protection. Only if competitors had exclusive access to the IP would a real threat be created. In this case a level playing field

may not hurt the market leader – the real competition is occurring on other fronts.

may not hurt the market leader – the real competition is occurring on other fronts. - Strategic Importance (SI): for innovations in non-core areas the best IP strategy can vary depending on whether those areas may later become important or if protecting them from competition is a strategic necessity. This may also include whether technical innovations should be fully and comprehensively exploited or given a more cursory exploration to understand potential and obtain minimal protection or establish minimal freedom-to-operate.

- Reverse Engineering Potential (REPot): For process, manufacturing, or chemical innovations where the consumer or competitor will see little difference in the product, the question of whether the innovation could be externally discovered through practice of the innovation must be considered.

- Commercialization Viability (CV): The likelihood of commercialization of the innovation should also be considered. Also, if the innovation is likely only to enable another innovation or invention the resource dedicated toward protecting it may not need to be as highly prioritized.

- Resource Intensity (RI): In organizations that are already very lean this discussion likely already occurs, however when determining the strategy to pursue the potential costs for creation of the IP as well as to maintain it (and possibly even to circumvent it if protection or FTO is not established) should be discussed. Resource intensity can include cost of creating, manpower needed to support, cost to maintain the IP

All of these considerations can be taken together to determine the best course of action. This will determine a Return-on-Investment (ROI) potential for the IP being considered. In fact, the entire strategic discussion could be reduced to an equation that allows further discussion on how the appropriate IP strategy is determined:

How can these criteria be used then to determine a path forward?

For situations where a very low IPROI is determined, simply doing nothing may be an option. If the innovation is not in a competitive arena, is not on-strategy, or is not enforceable, then the best use of resource could be to let the idea go.

For instances with a moderate IPROI the decision to patent, hold as a trade secret, or defensively publish can be determined according to the relative weight of the factors. An innovation found to have high strategic value and commercialization viability but low competitive intensity might be best protected through defensive publication, while in the opposite instance (high competitive intensity with high commercialization viability and low strategic importance) the value of a patent may be recognized. For projects with very low reverse engineering, potential trade secret protection could be the best route.

For scenarios with a very high IPROI going forward with a patent would almost always be advisable, though of course a number of instances where this is not the case can be imagined.

Obviously the area of IP strategy is a high importance to many organizations, however much of the focus in recent years has been on creating and managing large IP portfolios. For the osmotic innovator a better strategy is needed; one that balances resource scarcity with the need to create value for the company.

The Role of Psychological Priming in Innovation

I have a rather unique ability. I have the power to potentially alter your behaviour and perception of others by simply showing you a list of words. Impressed? Don’t be. In actuality I am simply applying a psychological technique called priming. Academically, priming is defined as “the process by which recent experiences increase the accessibility of a schema, trait, or concept.” Sounds confusing, but in reality it is very simple to understand. Imagine if I were to provide you with words like rude, intrude, and disturb to unscramble and then ask you to come get me when you were done. Upon completion of the task, you find me but notice I am having a conversation with a colleague. Would you immediately interrupt me or wait a few seconds? What if the words were patiently, appreciate, and polite? Would that alter your behaviour? Surprisingly, in a study performed by John Bargh and his associates, participants primed with aggressive and rude words overwhelmingly interrupted the conversation faster than people primed with either neutral or calmer words[1]. This is just one example from Social Psychology that demonstrates how our actions and thinking can be skewed based on how we are primed prior to encountering an event.

If we now think about the potential application to innovation, there is something rather interesting that comes to light. In any innovation session there exists a potential struggle between Management and the Employees. Management oversees the resources needed (e.g.: funding, personnel, allotment of time) while the Employees are the ones who will do the innovating. Should we consider a negative primer to something like the phrase “This is a very difficult innovative challenge and we may not get a lot of ideas”, a positive primer would then be along the lines of “This will be a rather easy innovation challenge and we should be able to get lots of ideas”. What if we were to use the negative primer for Management and the positive one for the employees? Would that provide a better innovative atmosphere? How about changing the combination and providing management with the positive primer and employees with the negative one? If we were to map out all the possible combinations, we obtain the following diagram:

There are several situations that can result from different combinations of positive or negative priming.

There are several situations that can result from different combinations of positive or negative priming.

Management Positive Primed: Trying to impress Management by informing them the innovative challenge will be easy counter intuitively produces a negative outcome as there will be limited funding and personnel.

Management Negatively Primed: This produces a positive result, as Management will now think the task is rather challenging and in order to successfully complete it, will provide extra funding and personnel.

Employees Positively Primed or Negative primed produces the results we would expect. Telling Employees they have been selectively chosen for the challenge due to their skill level and creativity will obviously produce a group that is very motivated and enthusiastic to take on the challenge. As one can easily guess, the opposite will occur if Employees are told the challenge will be rather difficult, many problems will be encountered along the way, and they were randomly selected.

Clearly there appears to be a combination that is optimal for an innovative environment: more resources are provided and the employees are very enthusiastic. This lies in priming management in a negative way and priming Employees in a positive way. As mentioned, this paradoxically should result in a situation where funding and/or additional resources are provided to an eager bunch of innovative employees waiting to take on the challenge. Imagine if all your problems were approached in this way!

There is also a situation that should be avoided. If management is positively primed, and Employees are negatively primed, low levels of resource and funding will be provided and you will end up with a bunch of Employees who do not want to take on the innovative challenge.

It can be agreed upon how either of the remaining two combinations (e.g. positive primer to both Management and Employees/negative primer to both Management and Employees) is what a typical company usually faces when an innovation challenge is encountered. Either there will be excited management ready to give money, time, etc to unmotivated and overworked employees, or very excited employees who want to work on a particular challenge will be told they have very strict limitations. However, as demonstrated above, perhaps utilizing psychological priming may decrease this tendency and help to promote a more positive innovative culture.

[1] Bargh, J., Chen, M., & Burrows, L. (1996). Automaticity of social behavior: Direct effects of trait construct and stereotype priming on action. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 71, 230-244.